It wasn’t so long ago that Maria would dread the prospect of a call from the hospital where her husband Imre had been forced to stay, for she’d had several that broke her heart. Restrained by several security guards, her husband, confused due to medication and dementia, would be pinned to the floor while the hospital team sought Maria’s permission to administer a dose of powerful antipsychotic medication. Unfortunately, this often happens when someone living with dementia expresses their frustration with threats of anger.

That type of phone call happened five times in the three-and-a-half-months Imre was in hospital. He lost 60 pounds during that period, tried to flee more than once and was only able to see his wife for two hours a week.

“It was a nightmare,” Maria says, but as she reflects upon the experience now, Imre is in a much better space. He is among 20 residents who live in a temporary Enhanced Supportive Neighbourhood at Erin Mills Lodge in Mississauga; like Imre, these residents were all deemed by hospital physicians to be high risk for “behavioural challenges”, and the red flags throughout the medical files prevented any long-term care home from accepting them.

To be clear, Erin Mills Lodge isn’t a behavioural care unit. It is simply a small LTC home that happened to have a floor empty and a team that understands that for people living with dementia, relationships, consistency and a gentle, respectful tone can be more effective than restraints, confrontation and antipsychotic medications.

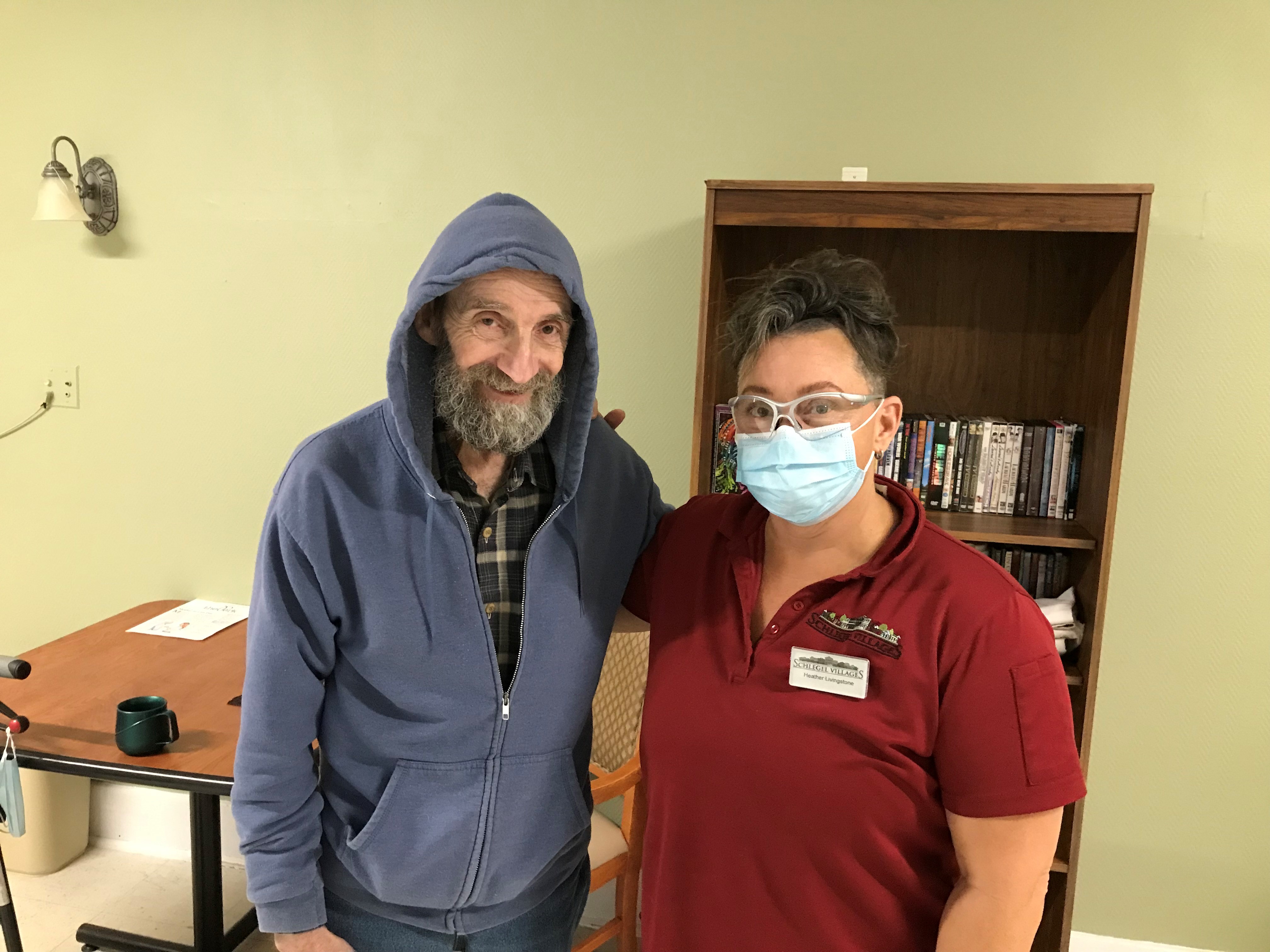

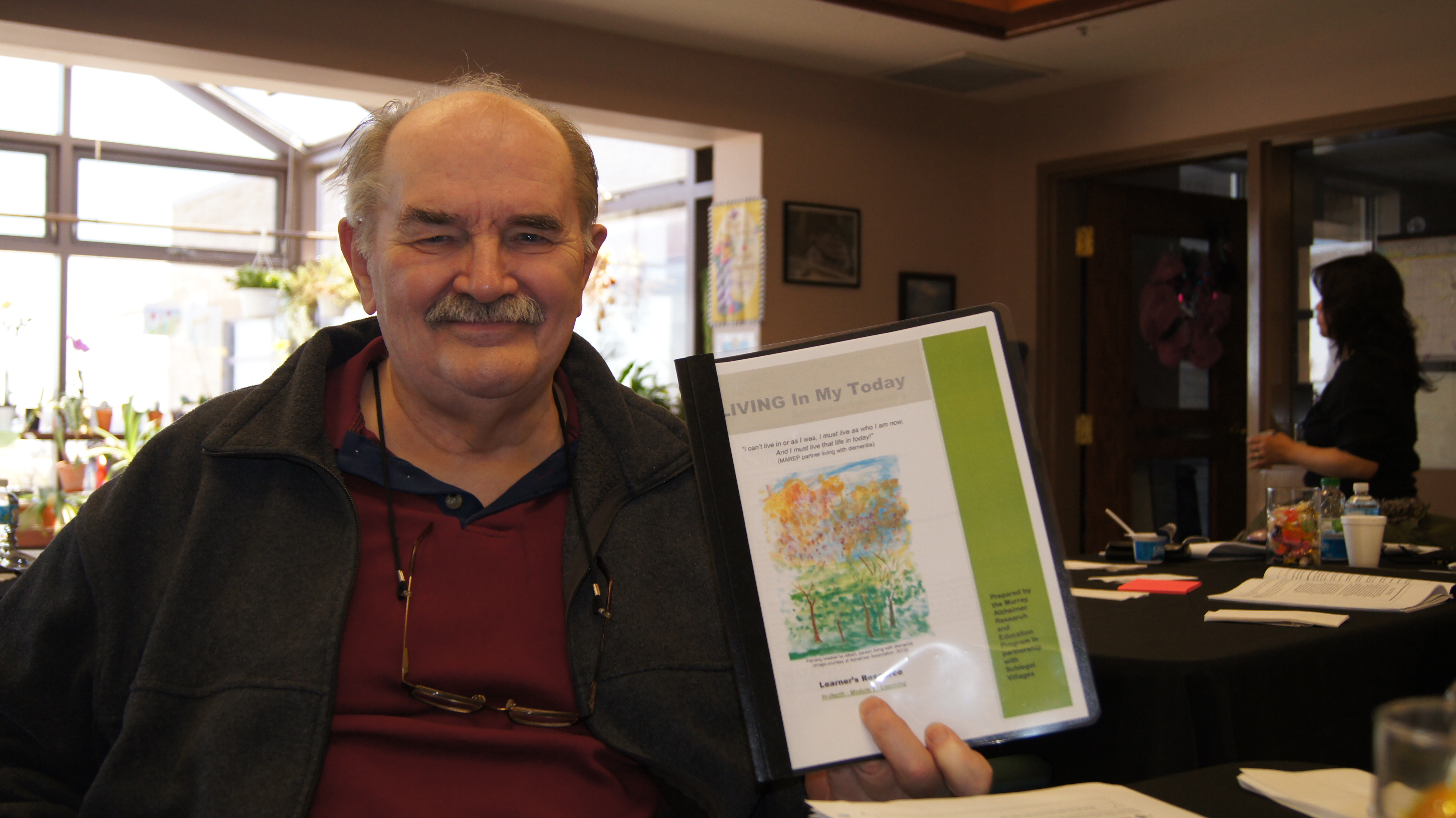

Heather Luth, Schlegel Villages' Dementia Program

Coordinator, has supported the Erin Mills Lodge Team through

the development of the Enhanced Supportive Neighbourhood.

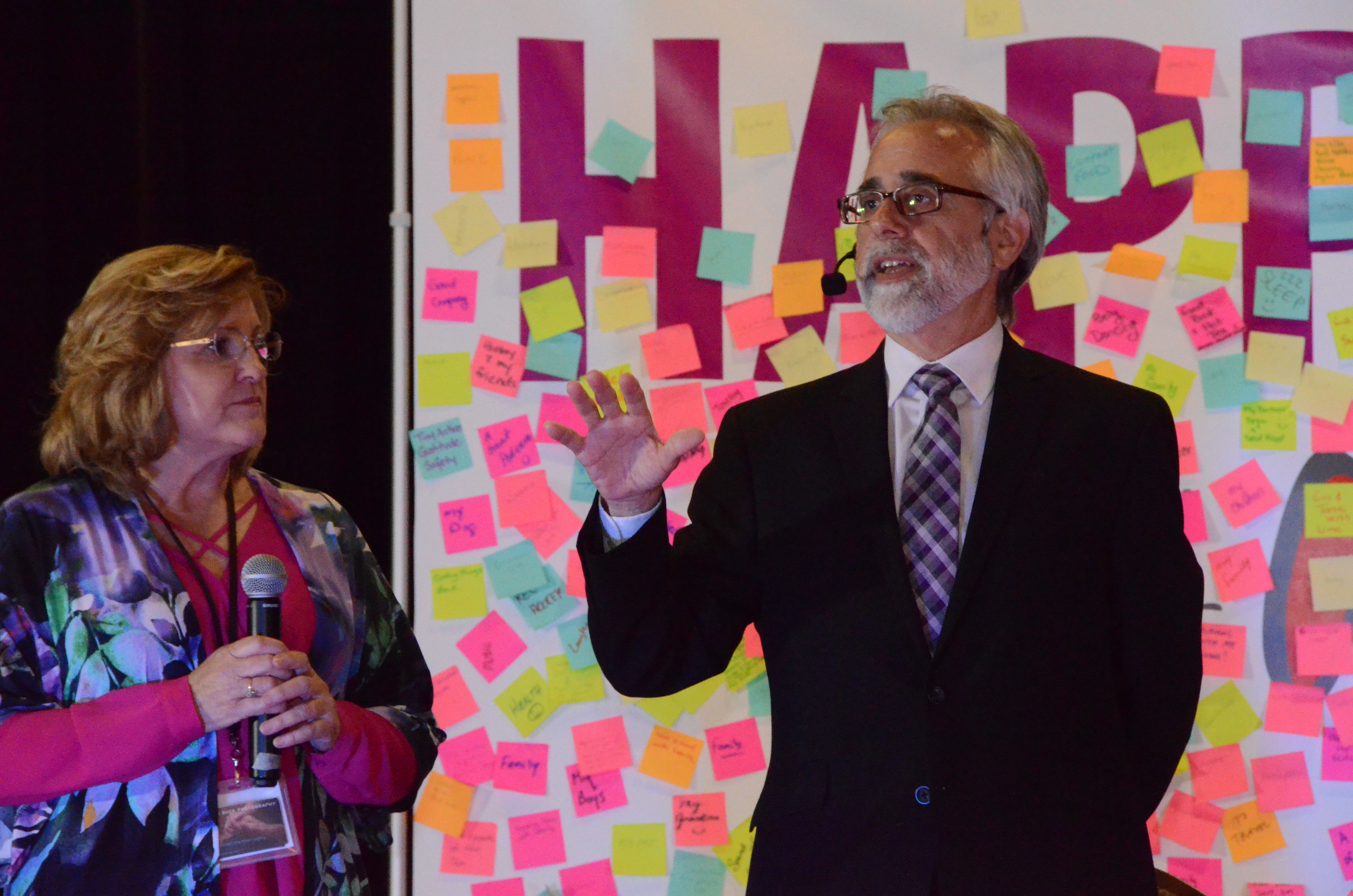

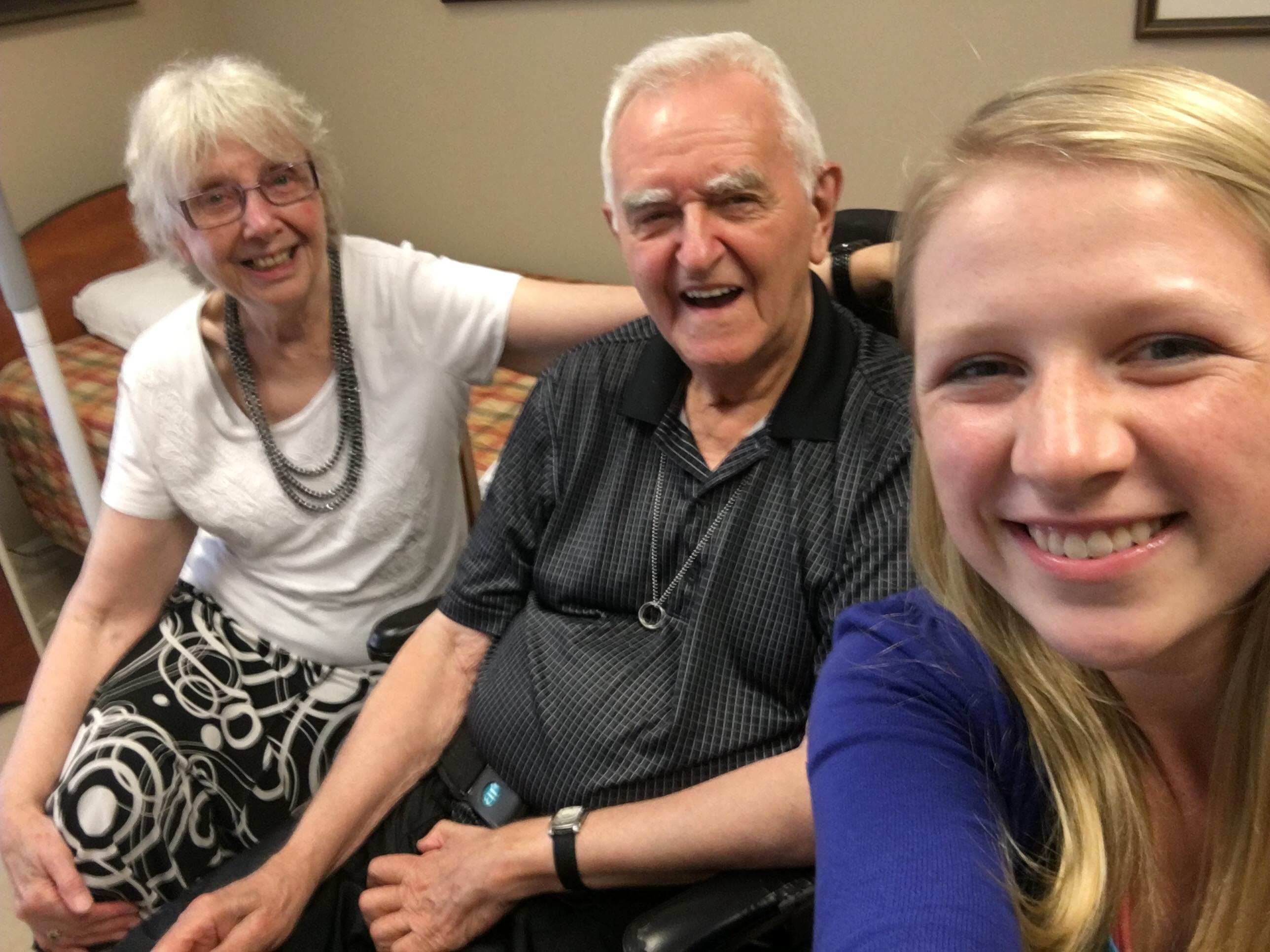

In the large lounge space upon the first floor of Erin Mills Lodge, Maria and three other ladies are gathered to share how the small home’s approach has transformed their lives.

Several of the home’s leaders and community partners have gathered to hear the insights as these four kind-hearted ladies describe how their husbands went from languishing in hospitals with little or no hope of transfer to an appropriate home, to living peacefully at Erin Mills Lodge. Heather Luth, the Dementia Program Coordinator with Schlegel Villages, is facilitating a day of discovery to highlight the many aspects of the ESN approach that are contributing to the success of the pilot, but it’s the stories these ladies share that truly highlight the impact.

“I am very happy we are here,” Maria says. “It’s like coming home to a family that understands me.”

When things were at their most difficult, it seemed nobody understood.

The five months Rosa’s husband Tomaso was in hospital was much like Imre's experience. Tomaso refused food and grew more confused with each passing day. Rosa was initially limited in her visits but after strong advocacy, she was able to visit daily to offer her husband some comforting Italian food.

“When I was there, he was a different person,” Rosa says. “Otherwise, he’d fight all the time with the nurse, with the PSW, and it’s harder to control him.”

Rosa’s voice quivers and her eyes well with tears when she describes the guilt she felt, but her strength is clear.

Today, she visits as often as she likes and while some days, it may take more time for him recognize her, their visits are meaningful and she knows Tomaso is well-cared for at Erin Mills Lodge.

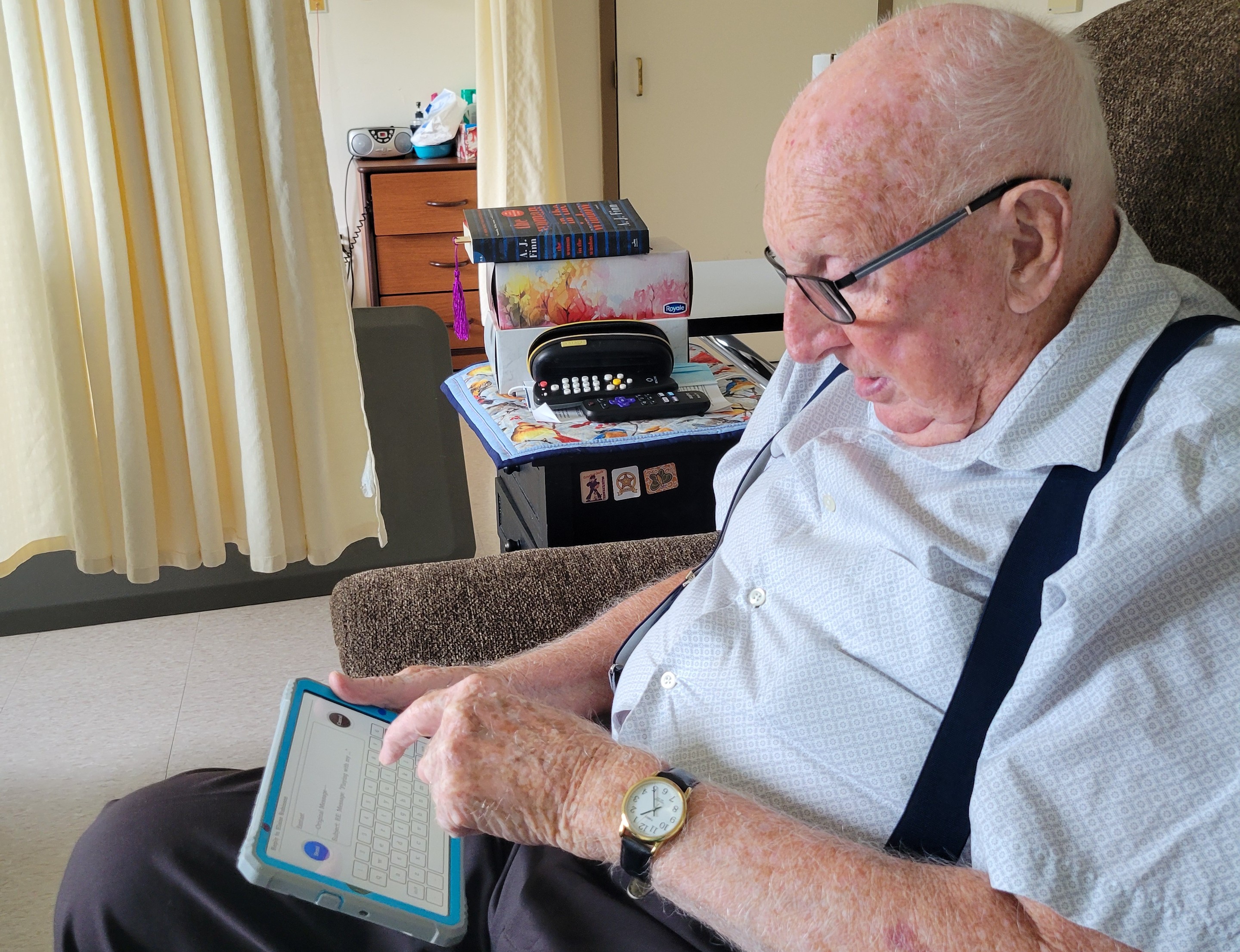

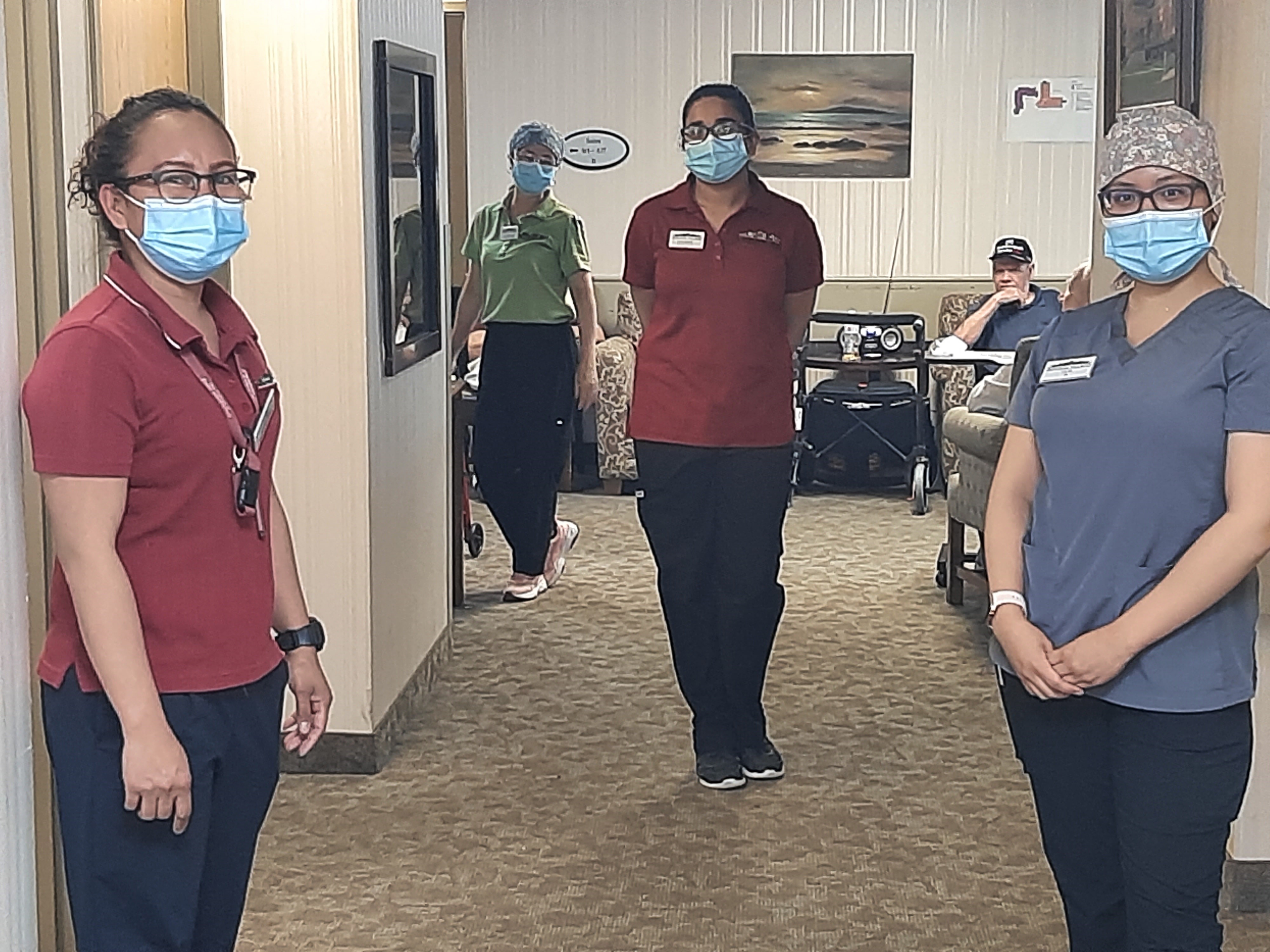

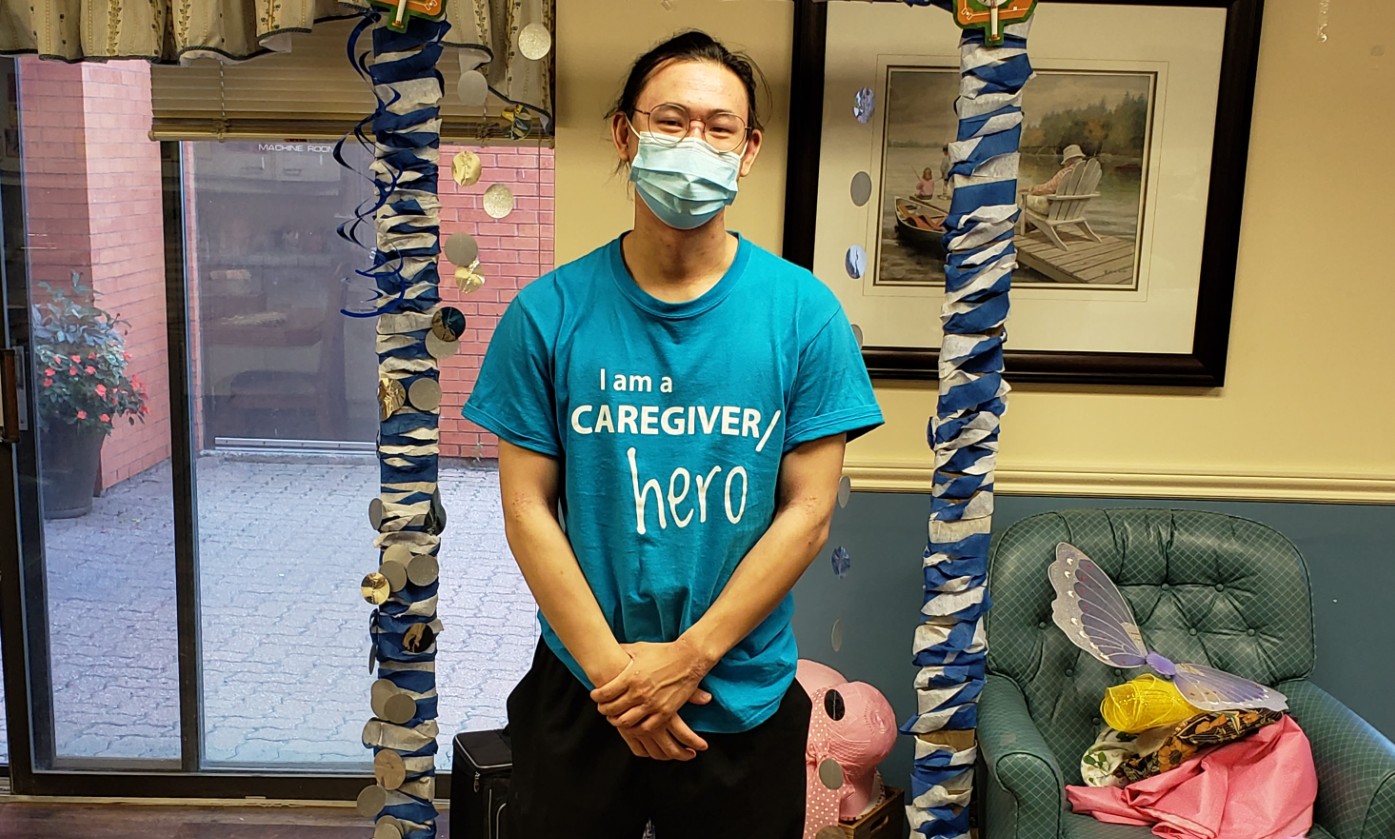

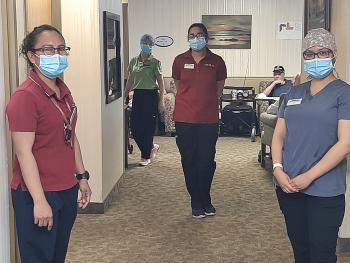

Team members work 12-hour shifts, meaning there are

fewer disruptions in the day and more consistent, dedicated

support, helping to earn the trust of residents. They know the

residents so well, which makes all the difference.

Marilyn speaks about what she sees in the team’s approach to the support of residents. It’s worth noting that team members work 12-hour shifts, meaning there is less turnover and fewer disturbances through the day and more consistent, dedicated support for her husband, Mike.

“When Mike left our home, he walked and he talked and he ate by himself,” Marilyn says, noting she took him to the emergency room suspecting a possible urinary tract infection. “When he came out of the hospital, he was in a wheelchair, his talking was very badly and he was being fed, and that was in a seven-week period.

“Mike is now walking on his own, he eats by himself and he talks. He doesn’t always make sense, but he does talk.

“And,” she adds with a soft a smile, “we danced.”

Simple things can go so far.

When Mike was diagnosed with dementia, the couple toured some of Oakville’s long-term care homes, planning for the future. What Marilyn wanted to see was team member interaction and a sense of true caring.

“We didn’t see staff around at a lot of the homes,” she recalls. “Here, the staff talk to (residents) and they touch them – all very important to me. They don’t walk by them without saying something to them.”

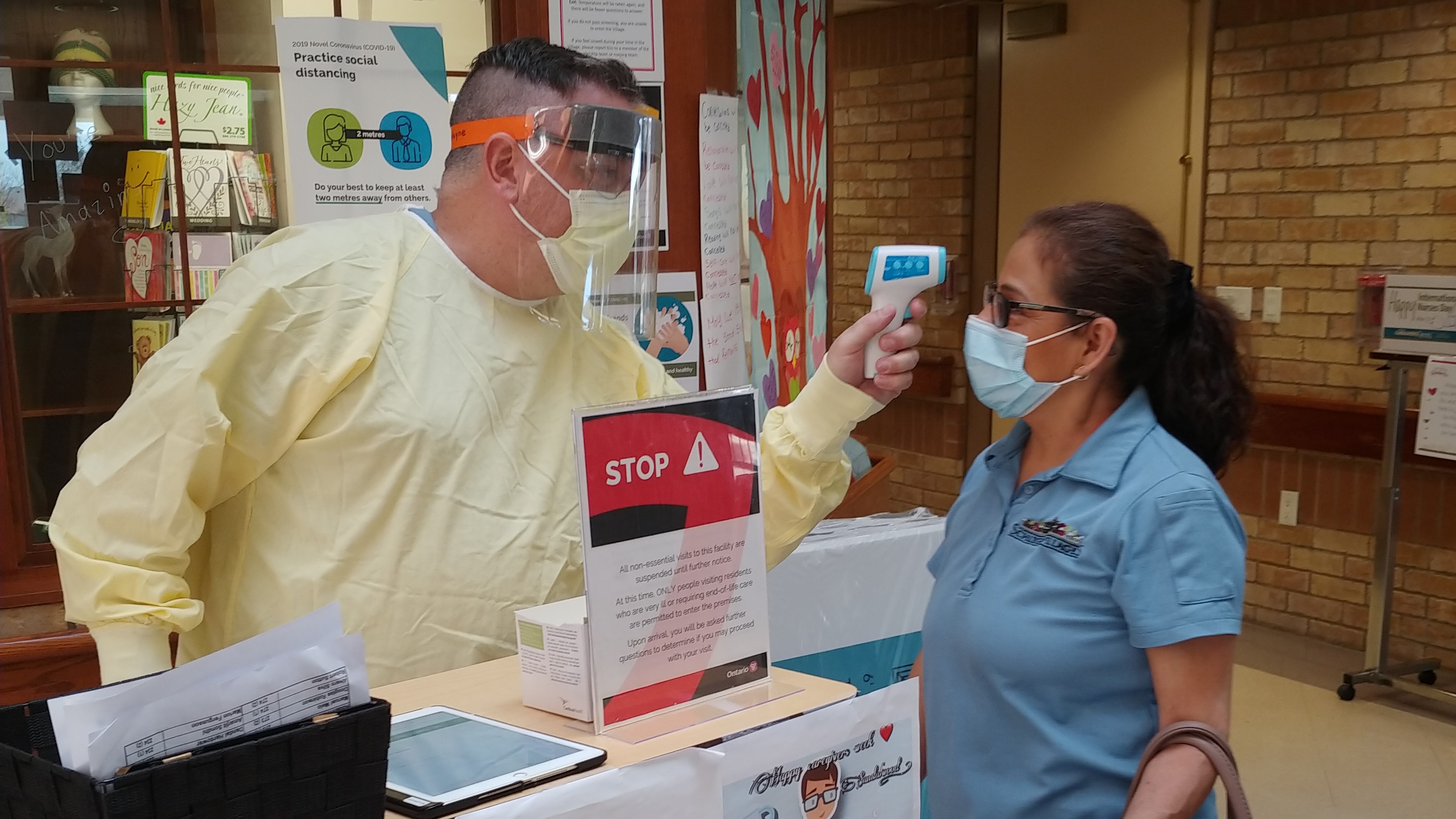

In the span of 10 days, Erin Mills Lodge prepared this neighbourhood for 20 residents with complex needs. This is not a fancy new building with all the amenities, but it is filled with people who understand the unique, individual nuances of dementia, and that is what counts according to experts.

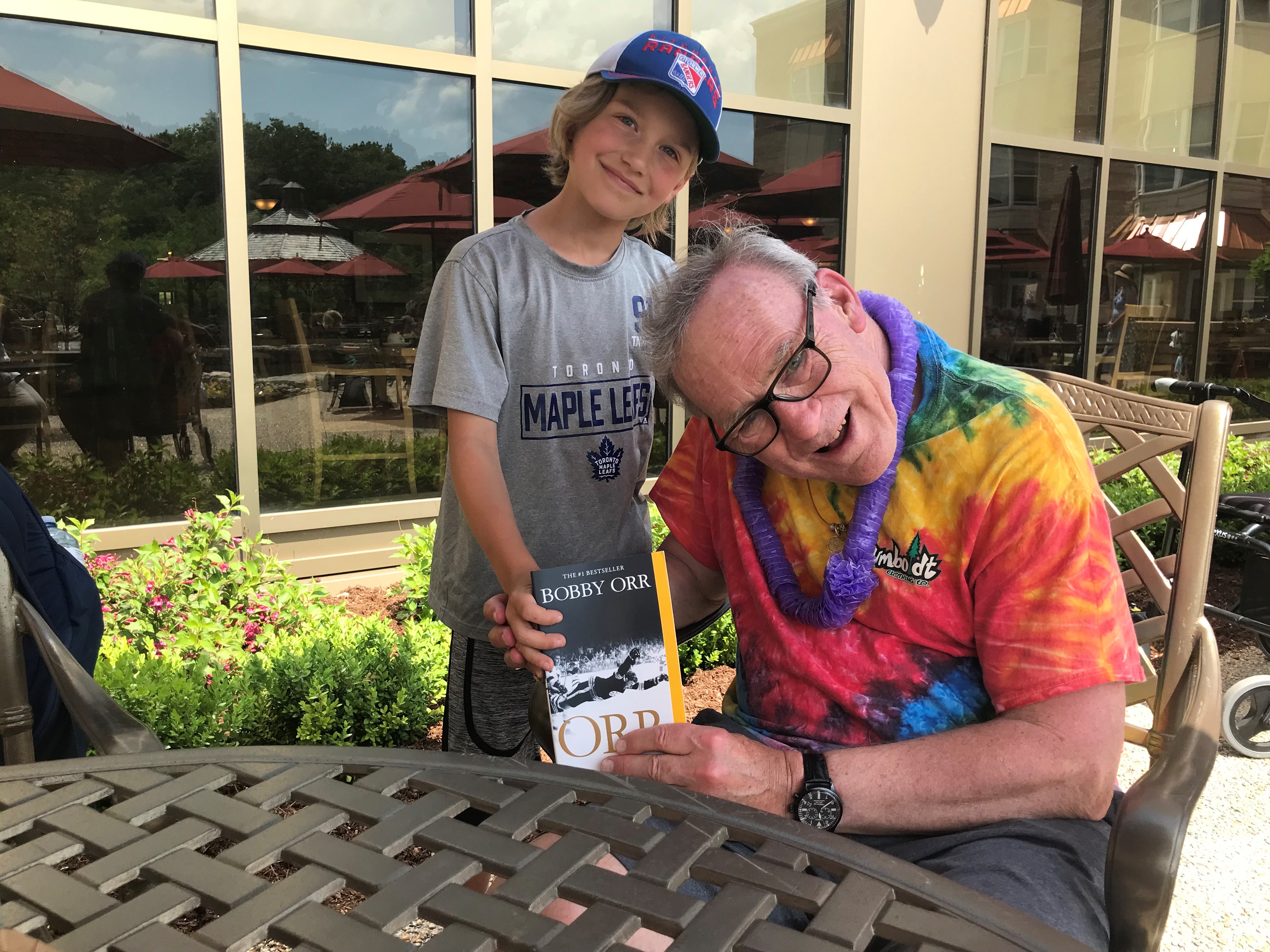

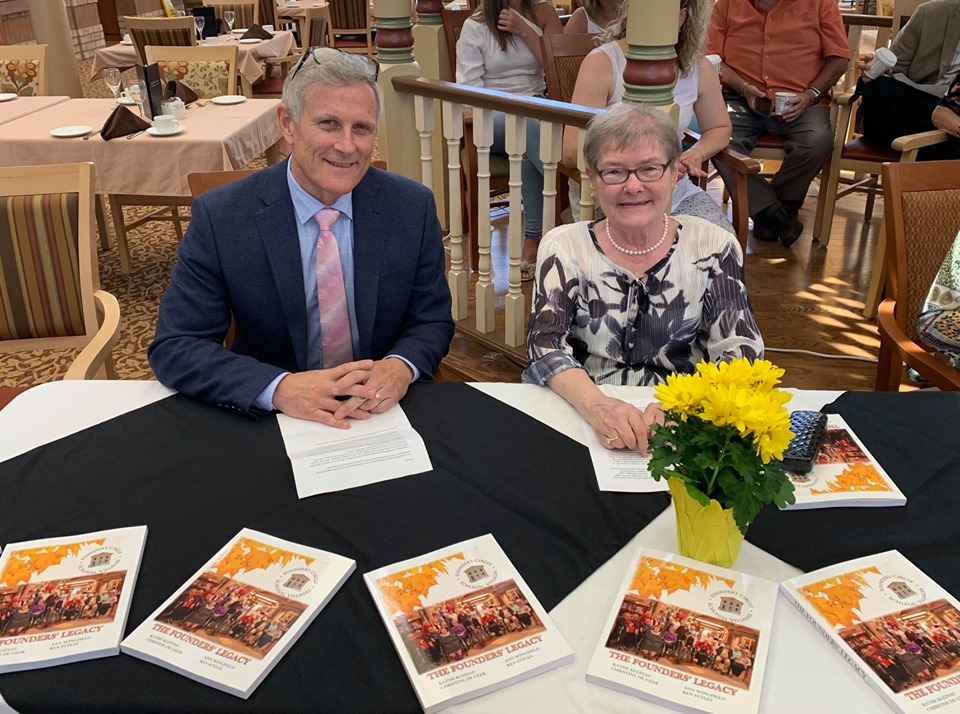

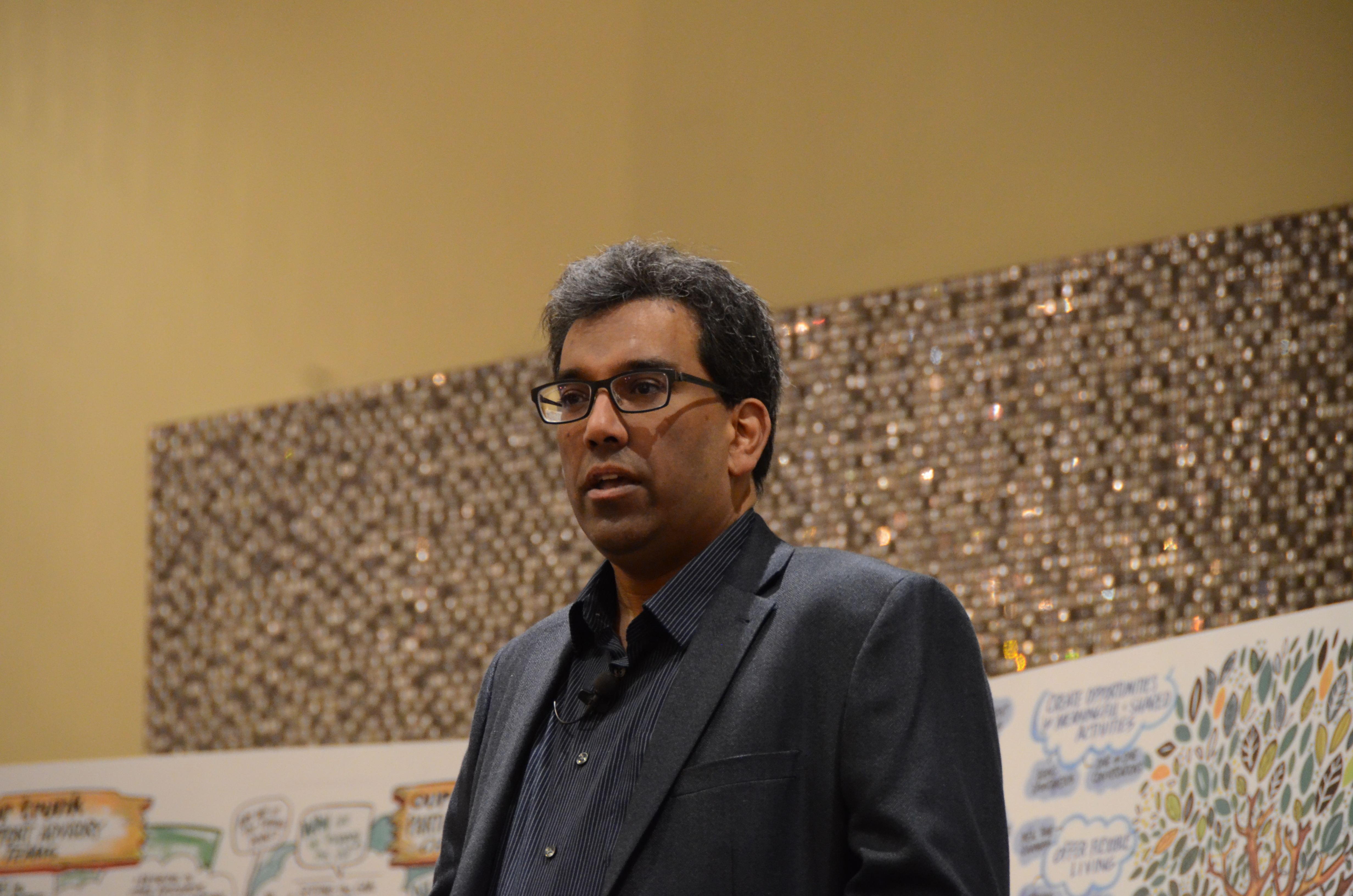

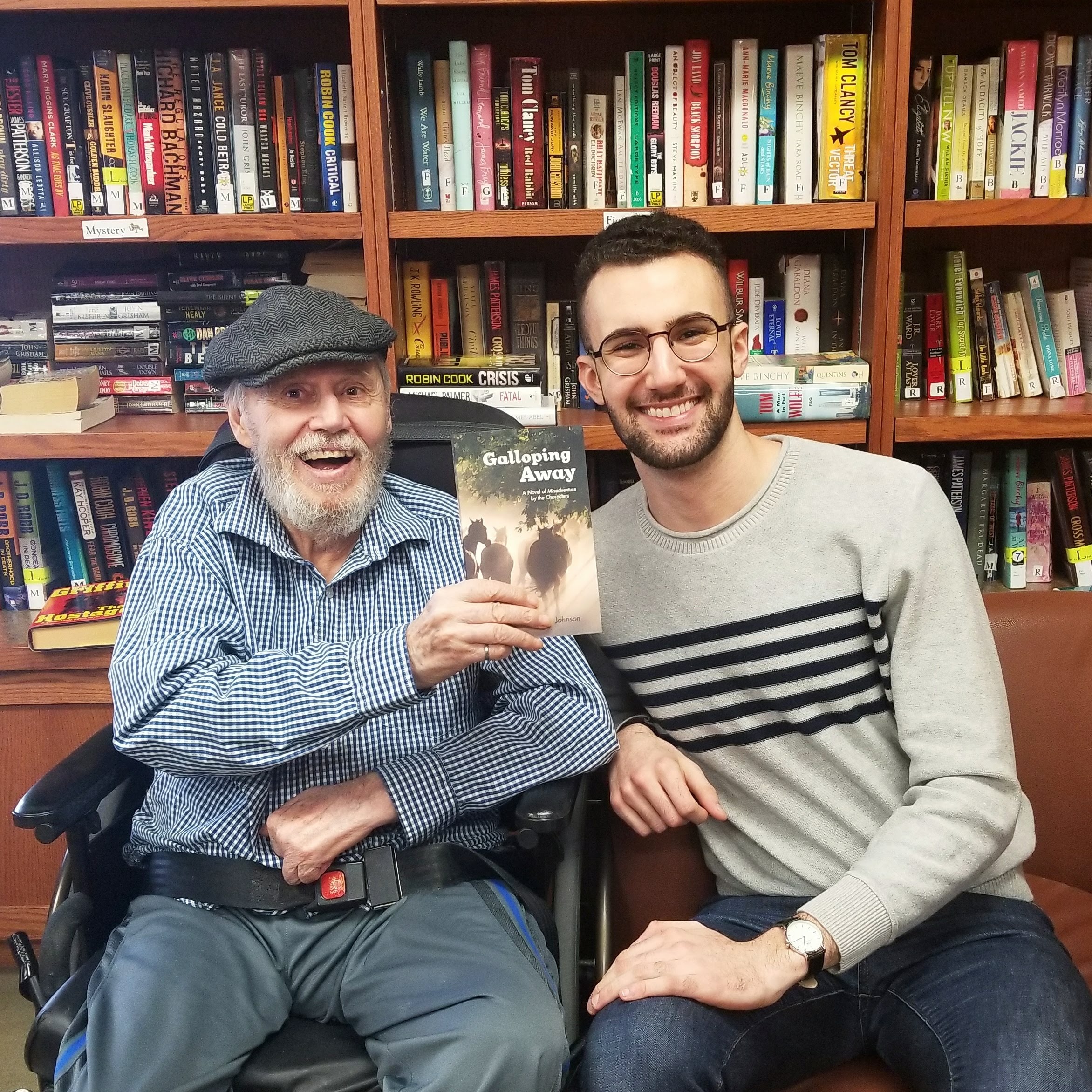

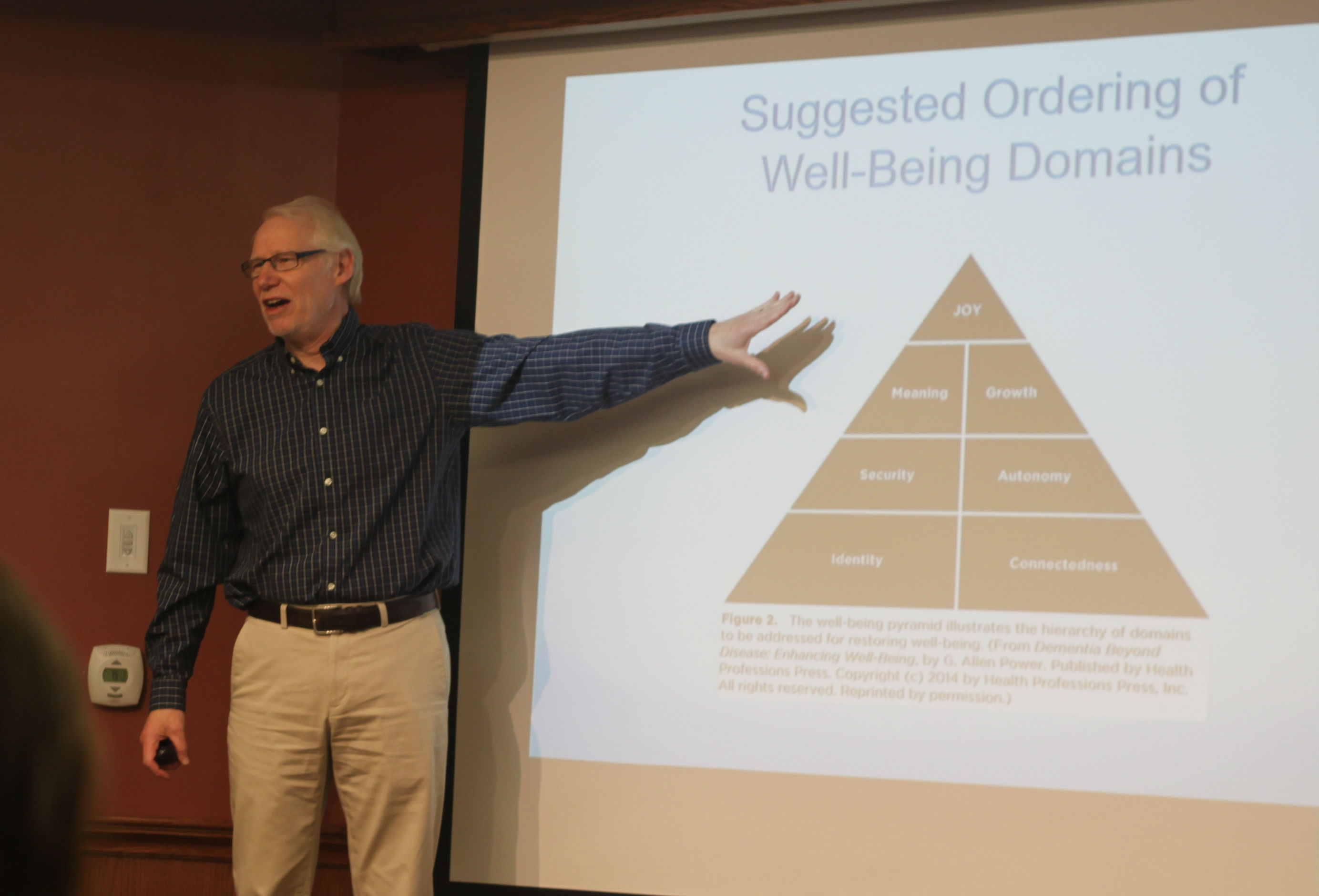

“The best way to tour a home is with a blindfold on,” says Dr. Allen Power, an internationally-respected dementia specialist, author of Dementia Beyond Drugs and Dementia Beyond Disease and the Schlegel Chair in Aging and Dementia Innovation with the Schlegel-UW Research Institute for Aging. “Don’t worry about the fancy chandeliers and all the trappings; just close your eyes and see what sensation you get. Does it feel like a place you want to be at or does it feel like a place you want to run away from as fast a you can?”

Dr. Power is visiting Canada for the first time since COVID struck, and he wanted to see what the team had accomplished at Erin Mills Lodge.

“Considering the population you are serving and the way the residents were marketed to you when this all started, nobody would walk up there and think that the people living there had any more challenge than anybody else living in long-term care,” he tells the Village team after touring the neighbourhood.

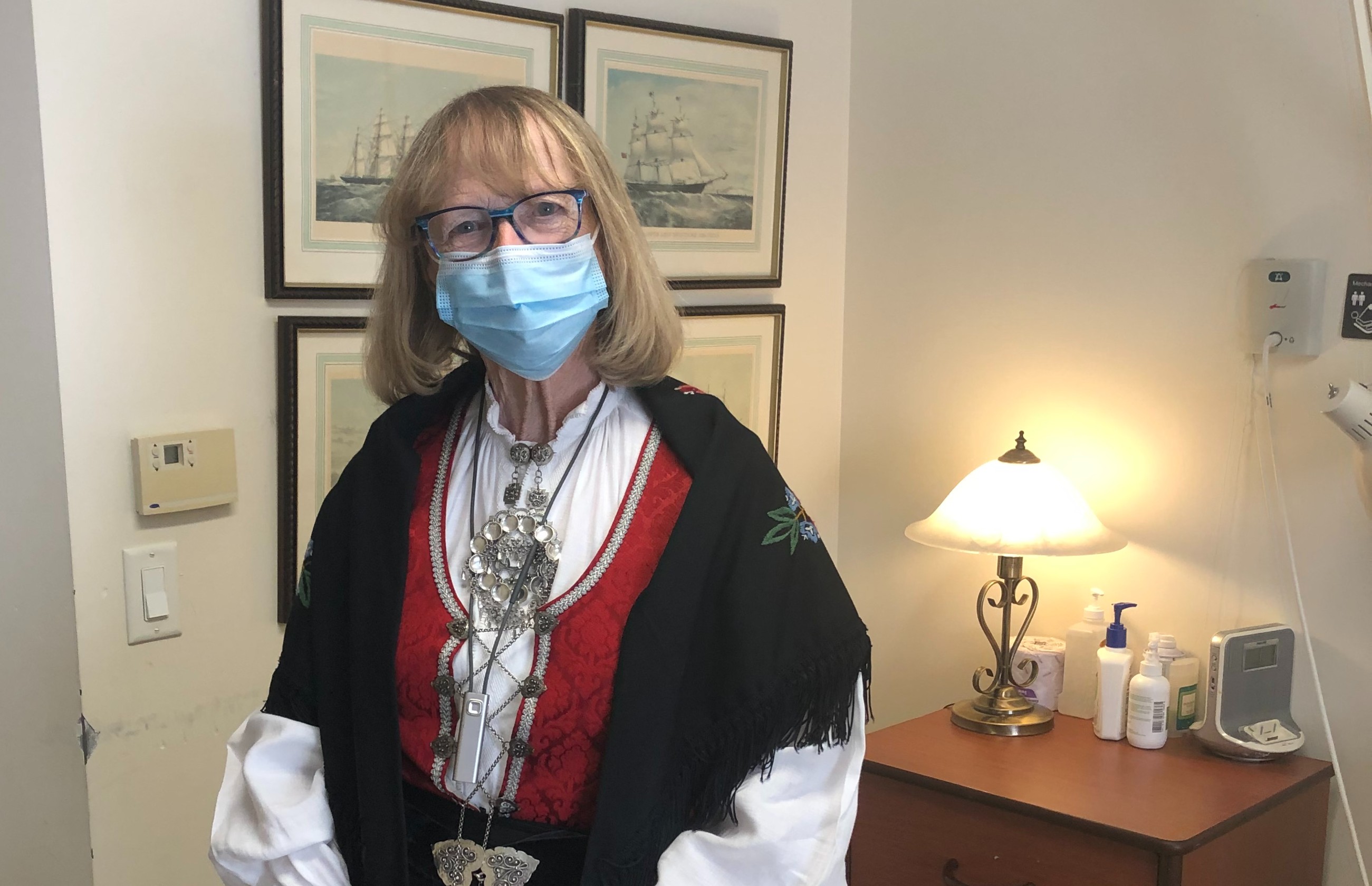

Dr. Al Power says the EML team should

be proud of the difference they are making

in the lives of the people they serve.

He doesn’t blame any hospital or practitioner for the way they approached Michael, Emery, Tomas or Catherine’s husband John – he just notes that a hospital is the last place such people should be housed because they are designed for acute illness and recovery.

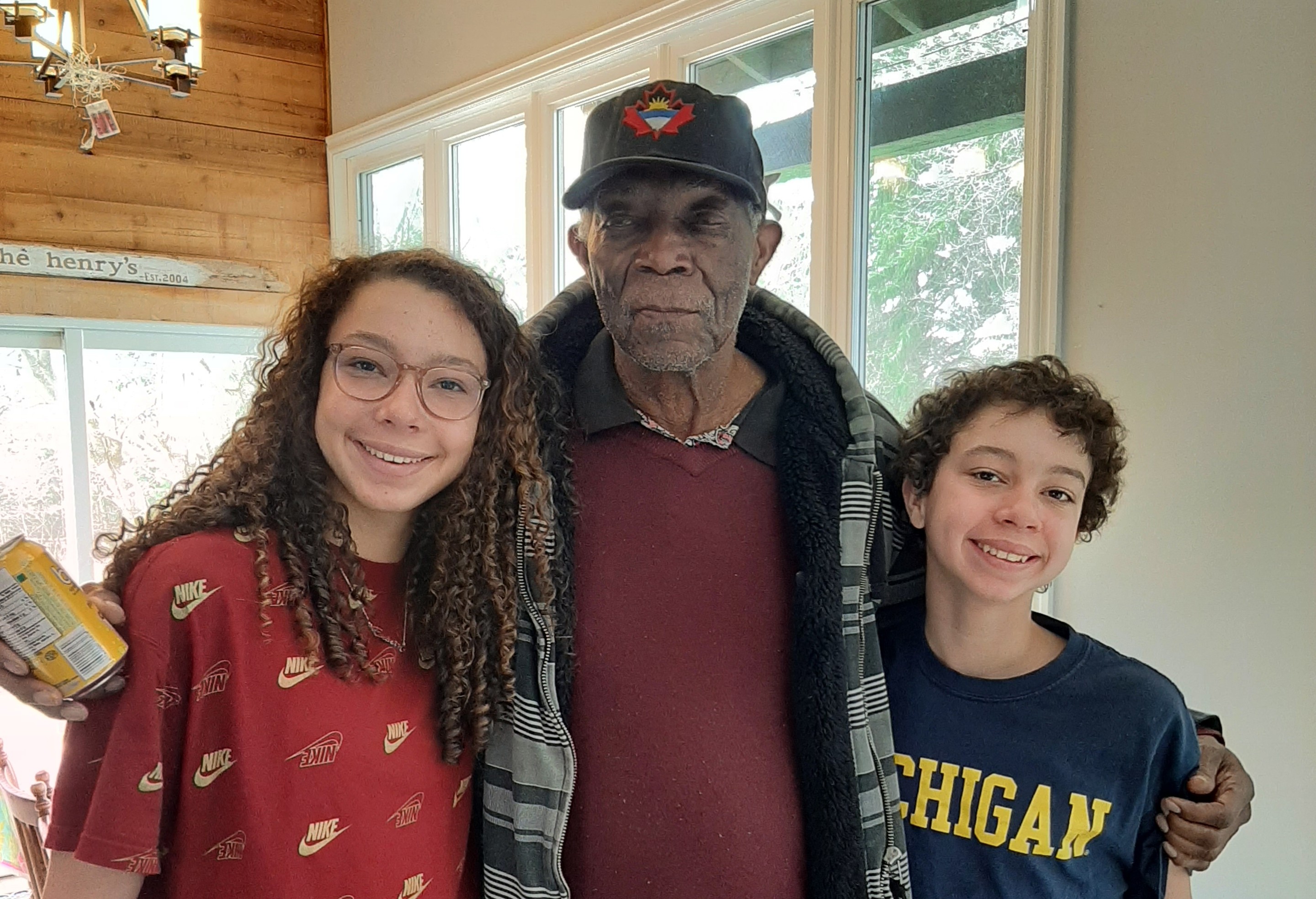

Though the residents who have come to

Erin Mills Lodge were deemed to be a

risk elsewhere, with the right engagement

and understanding, they are living just as

any other person might in a typical

long-term care environment.

“What people need after six months in the hospital is emotional rehab,” says Dr. Power. “People have been traumatized and they need a place that’s calm where they can just get back to life again, because being in a hospital is great for acute illness but it’s no place to live.”

Andrea Oattes is a Behavioural Supports Ontario case manager serving Halton and Mississauga. She has helped transition several people from hospital through to Erin Mills Lodge and, in some cases, on to a permanent home in other long-term care settings.

“The beautiful thing that we’ve observed is that these people are in the perfect environment and it’s kind of neat to be able to see what’s possible, because you lose sight of that,” Andrea says. “We’re so clinically-focused in managing the ‘behaviours’ that you lose track of what you can do if you step back.

“In the hospital,” she adds, “somebody who has dementia and has functional ability . . . is seen as a problem because they are ‘wandering,’ and they’re ‘exit-seeking’ and we label them as such, so we’ve used medications or restraints to make that not happen. When they come here, we see (functional abilities) as positives.

“The stigma we all have the belief we have is that when you have dementia, you will just lose your abilities, and that gets mixed up in the hospital,” Andrea says.

As a geriatrician working closely with geriatric psychiatrists in both LTC and hospital settings, Dr. Ahmad von Schlegell, Chief Medical Officer with Schlegel Villages, says the Erin Mills Lodge approach will be critical for the entire health system in addressing the rising prevalence of complex dementia in an aging population.

“I just feel lucky that I’m working with all of you because it’s the relationships that you guys all have with each other and with our residents that has made this all possible,” Dr. von Schlegell tells the team gathered in the lounge. “It’s the relationships that we have – the love that we have for the residents – that has made the biggest difference.”

The final guest to speak from her experience is Catherine, who felt such relief when her husband John was taken to hospital because she truly feared his expressions could turn more dangerous. The hospital team did their best and he had an excellent PSW there, but she says he was never encouraged to do anything for himself, and his abilities swiftly declined.

At Erin Mills Lodge, the PSWs are the ones who know John best, Catherine says, and she gets her information from them. She’d like to see stronger communication from the clinical team, but this is something the team can easily improve upon.

Dementia is a complex, progressive illness and the four loved ones who share their valuable insights and experience shed light on what is possible when the person is seen first instead of their diagnosis.

As a pilot project in partnership with several hospitals, BSO, Ontario Health and the Ministry of Long-Term Care, the Enhanced Supportive Neighbourhood at Erin Mills Lodge is showing remarkable promise. It’s a place where the team feels hope for those they serve, and they do so with love, which translates into enhanced life quality for everyone connected to it.